To Embed or Not Embed an Index in Word, InDesign or Quark Xpress!

To Embed an Index is a popular option when it comes to indexing. What are the advantages, and disadvantages of using that type of indexing?

You want to get the index to the book that you are working on done relatively quickly. You also want to be able to reuse the index if you later publish another edition of the book. And since you plan on producing both a print and an eBook version of the book, you want the index to work in both.

If you are trying to achieve any or all of these objectives, then by now you have probably already heard about embedding indexing. Here’s the skinny on what it is and a few words on the advantages and disadvantages that you’ll want to consider.

What is Embedded Indexing?

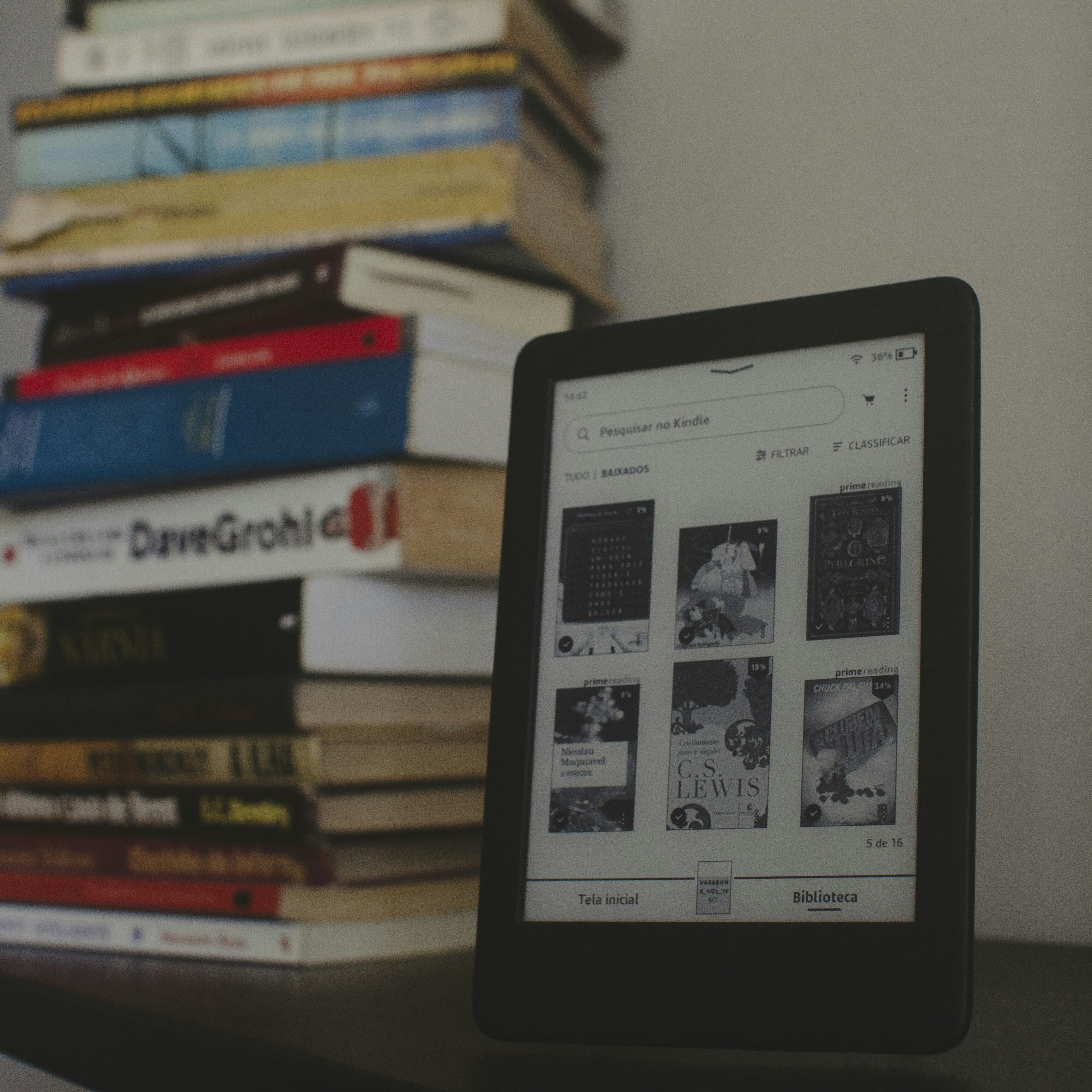

Embedded indexing is the process of inserting hidden tags, which contain index entries, into the text of a book. This can be done in most publishing software such as InDesign, Quark Xpress, FrameMaker and even in Microsoft Word. The tags can be viewed by clicking on an option within the application, but obviously they would not be viewable in the final output files, such as PDFs or eBooks.

Advantages to Embedded Indexing:

There are several advantages of embedding index entries into the text. One benefit is that it allows indexing to start before the book is even finished being written. You can send the chapters to the indexer one at a time and she can embed the index entries and send the chapters back to you. Even if you edit the chapter, deleting some sentences and moving some paragraphs around, the index tags get deleted with the text that you deleted and move with the text that you moved.

Also, since the index entries are embedded in the text, it doesn’t matter that you haven’t formatted the book yet, or inserted all of the images, etc. When the book has been copyedited, proofread and is ready to go, you generate the index and the page numbers after each index entry will reference whichever page where the corresponding hidden tag is located. The indexer will need to do an edit of the index, but that should only take a few days in comparison to the few weeks she would need to start indexing toward the end of the production cycle.

The other benefit is the point we mentioned at the beginning of this article: you can reuse the index if you wish to also produce the book as an eBook or in some other format. Since ePUB books don’t have page numbers per se, the index would also not have page numbers, but it would link directly to the text, taking the reader to the exact paragraph referenced by the index entry.

Disadvantages of Embedding Indexing:

Despite the benefits, there is a downside to embedding indexes in publishing software. One of them is that it is harder for the indexer to create the index. Since she is receiving the chapters one (or a few) at a time (and sometimes she might be expected to turn them in batches), she’s sort of indexing with tunnel vision.

She can view the index for each chapter that she is working on by generating it for that specific file, but she cannot see the index entries to chapters that she has already indexed to see how each entry should be adjusted to blend with the others. If she were working off of final PDFs, she could compare an index entry that she is writing to one that she created for a previous chapter, evaluate whether they relate to the same thing and then edit the old or the new entry so that they don’t conflict.

As a simple example, perhaps chapter 1 discusses “cooks” while chapter 7 uses the term “chefs”. Are they the same? Perhaps they are used to refer to the same profession in this book or maybe there is a distinction. If they are the same, the reader should not find two separate entries (one for “cooks” and the other for “chefs”) with completely different indented subentries under each of them.

Instead, the most commonly used term (we’ll say its “chefs”) should have all of the corresponding subentries and the other term (“cooks”) should have a cross-reference reading “See chefs.” If they are different, than both entries should have their own, distinct subentries. However, each entry should have a “See also” reference pointing to the other entry, since they are so closely related.

Editing a Difficult Index:

You can see how hard it would be to determine how to treat related entries in an embedded index. Obviously, there are much more complicated relationships and many synonymous or seemingly-synonymous terms throughout the text of most books, especially in highly technical works.

Editing the index, which needs to be done when the book is almost finished, is also much more difficult when the index has been embedded. Instead of being able to index as she goes along, comparing one entry with another, the indexer must clean up an index that, by now, has surely gotten rather messy. The best quality indexes are usually produced when the indexer can make many small adjustments during the indexing process, not by doing major edits all at once.

That being said, there are methods of saving index entries from previous chapters and then comparing them with new index entries upon creating them. Such an indexing system can help the indexer to avoid scattering information throughout the index and thus create a neater, more-organized index that needs less editing. But not all indexers know how to do this. (More on that in another post).

Making the Decision:

So what did you decide? To embed or not to embed? If you are still undecided or have more questions, contact us, and we’ll gladly answer your questions (at no charge) about embedded indexing.

0 Comments